CHALLENGE: Develop a lithium–sulfur battery cathode that improves practical performance.

SUMMARY: Lithium–sulfur batteries offer significantly higher theoretical energy density than conventional lithium-ion systems, but in practice much of that sulfur never gets used. Through early testing and literature review, I found that performance was often limited not just by chemistry, but by mechanical failure at the cathode–current collector interface. As the battery cycled, the cathode layer degraded, electrically isolating sulfur that should have contributed to capacity.

This shifted my focus from purely electrochemical optimization to how the cathode was physically built.

COURSE/CLIENT: Coherent Corp.

COMPLETION: March 2025

SKILLS: Materials processing, chemical and sustainable engineering, mechanical design for reliability, experimental testing & data analysis

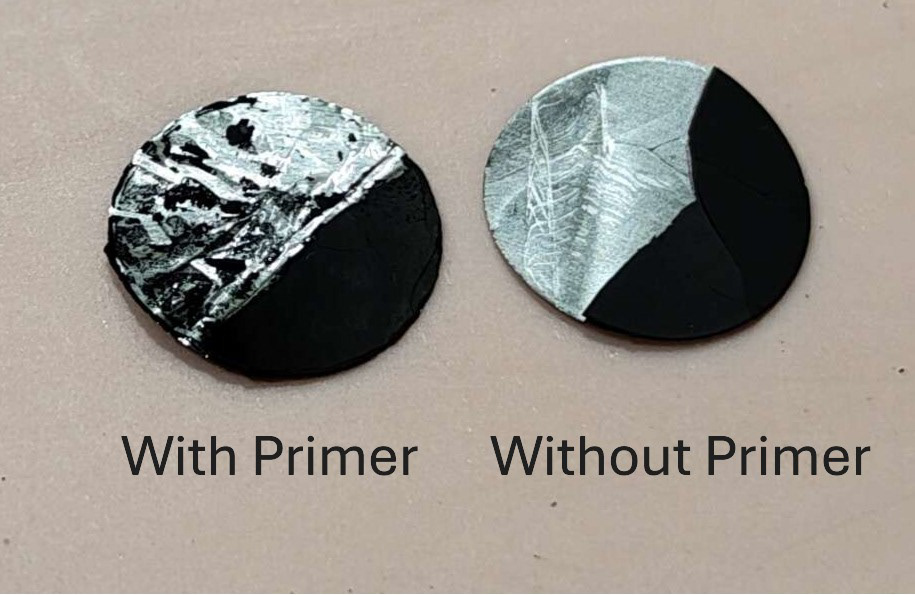

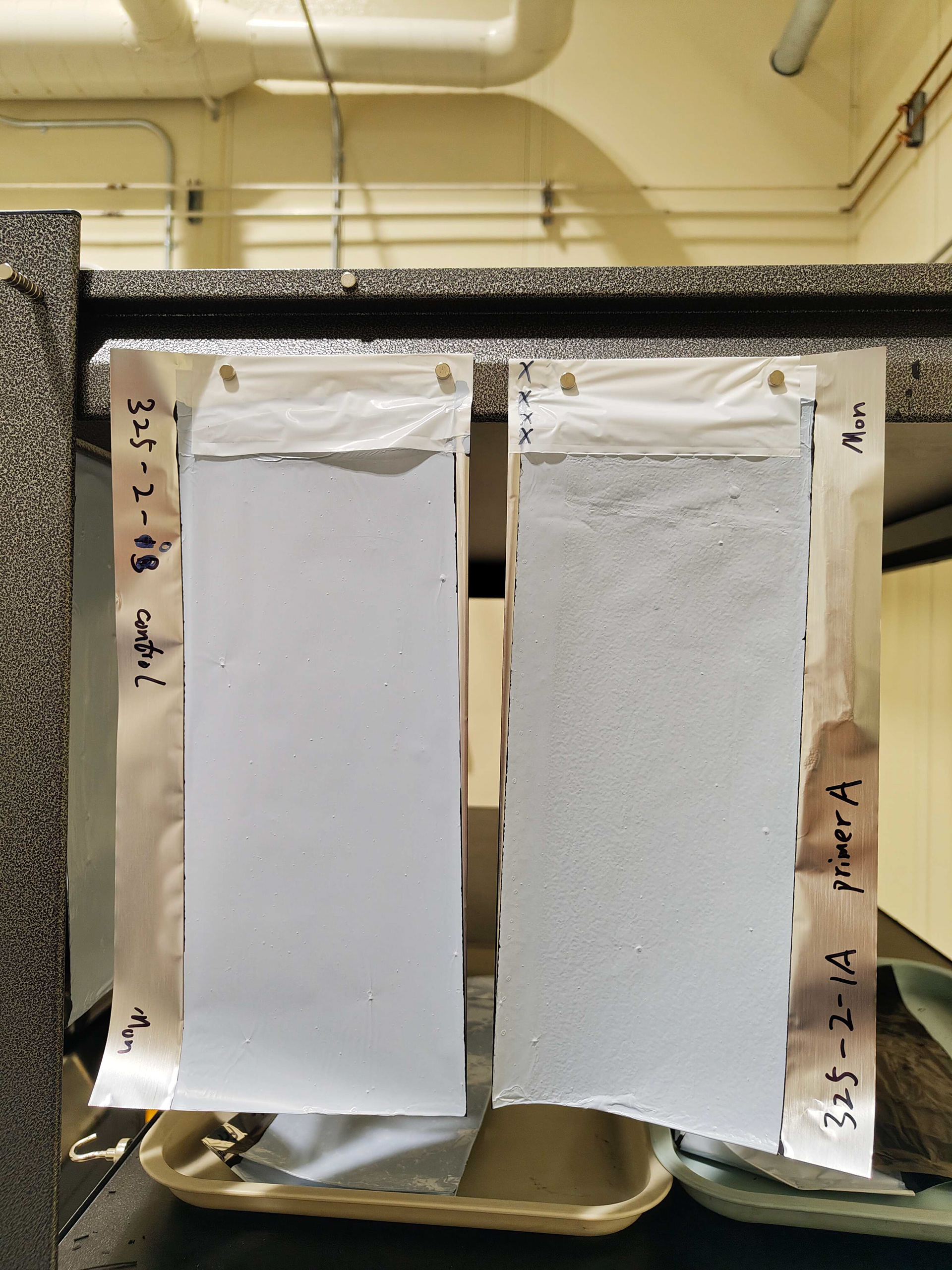

Cathode with primer

Cathode without primer

Scratch test on coin cell cathodes

Conventional cathodes use a single composite coating—sulfur, carbon, and binder applied directly onto aluminum foil. While simple, this structure forces the binder to perform two roles at once: holding the active material together while also adhering it to the metal substrate.

Inspired by traditional painting techniques, where a primer layer anchors paint to a surface before color is applied, I introduced an inactive primer layer at the current-collector interface. This created a graded cathode structure that concentrates binder near the aluminum foil to improve adhesion, while positioning sulfur-rich material closer to the anode to maximize electrochemical accessibility. As a result, batteries fabricated with the primer layer operated at a higher average voltage than those without it, indicating improved active material utilization and more stable electrochemical behavior.

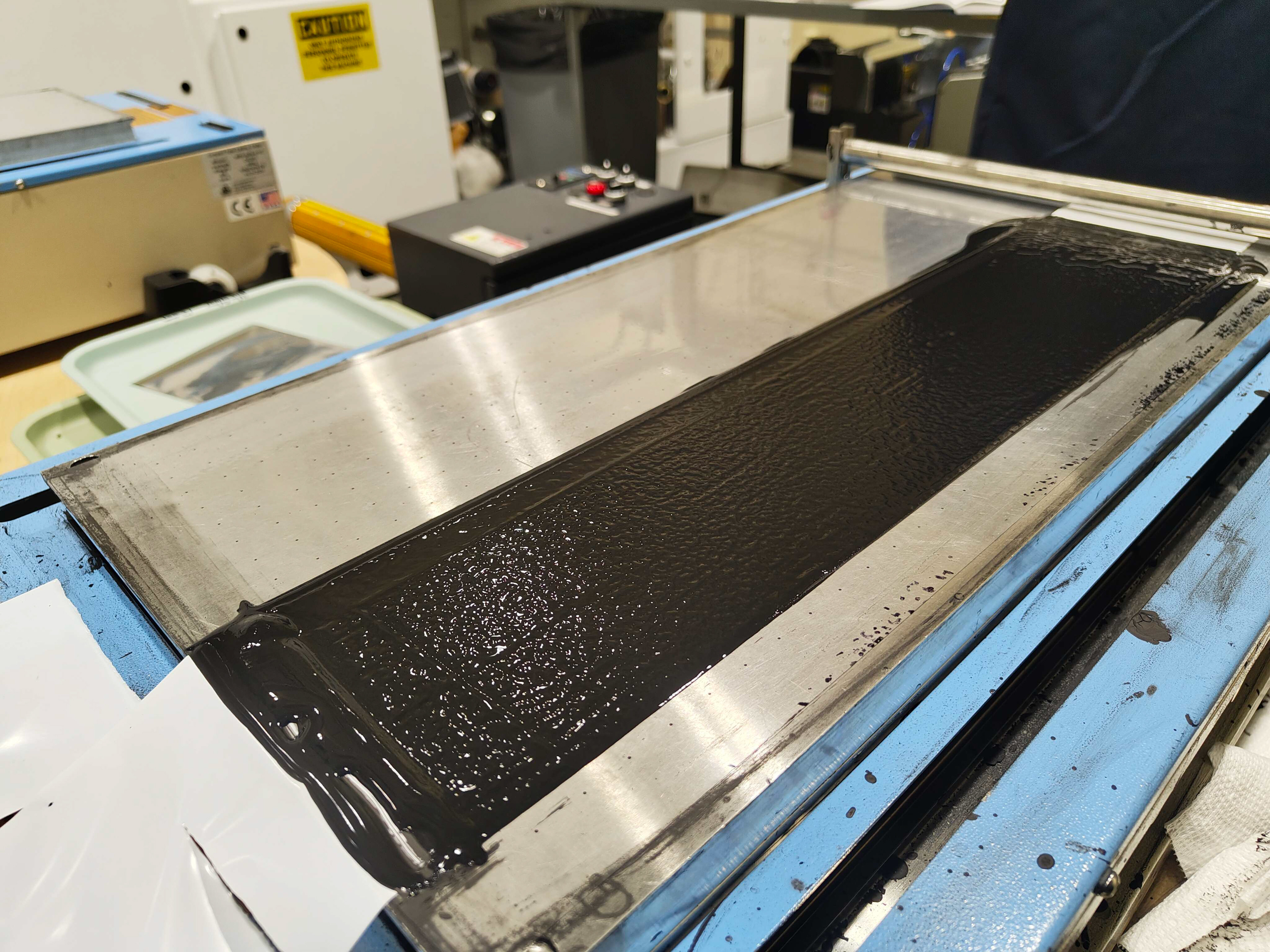

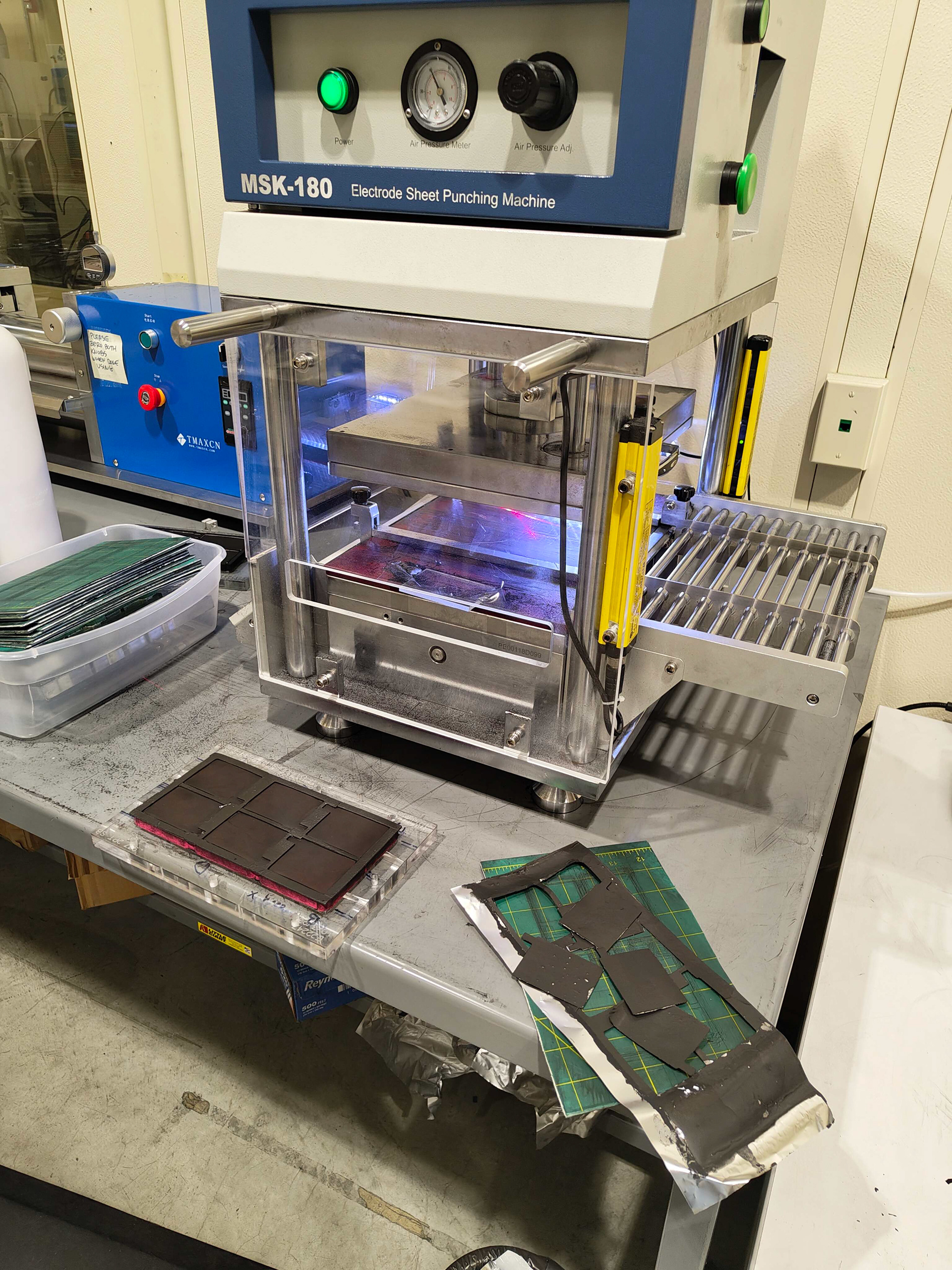

I fabricated clean cathodes using a two-step doctor blade coating process: applying the primer slurry first, followed by the active sulfur slurry. After drying, the sheets were stamped into electrodes. The stamped cathodes are assembled into pouch and/or coin cells, which are then subjected to formation cycling followed by extended electrochemical cycling. Cell performance metrics such as capacity, charge rate, and cycle life are monitored throughout testing.

To evaluate adhesion, I first performed qualitative scratch tests. Without the primer, the cathode layer readily flaked off the aluminum foil under mechanical stress, rendering portions of the active material inaccessible. With the primer layer, material remained intact even after deep scratches. I then used a cross-cut adhesion tester for quantitative metrics.

Doctor blading

Drying

Stamping

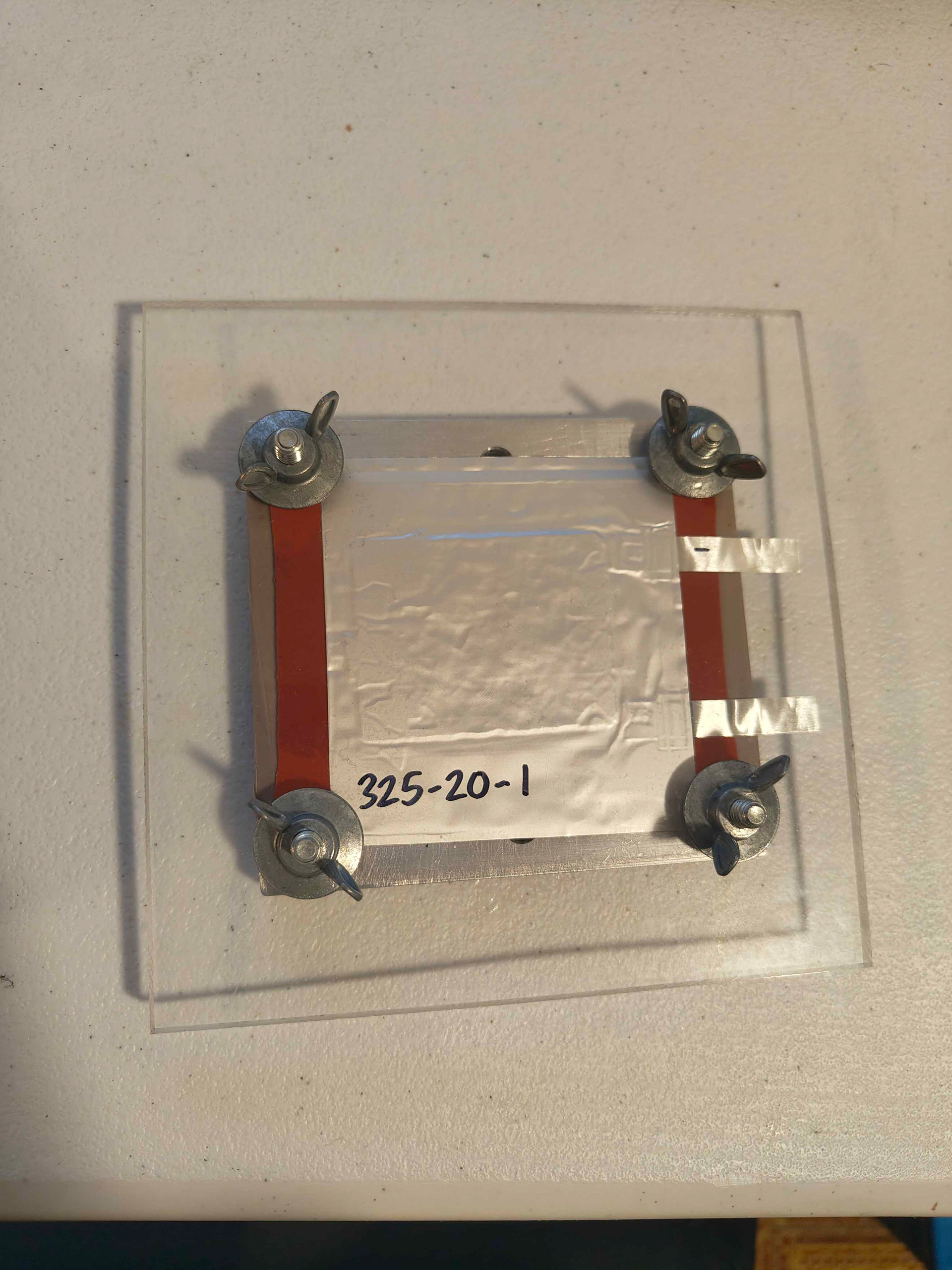

Pouch cell

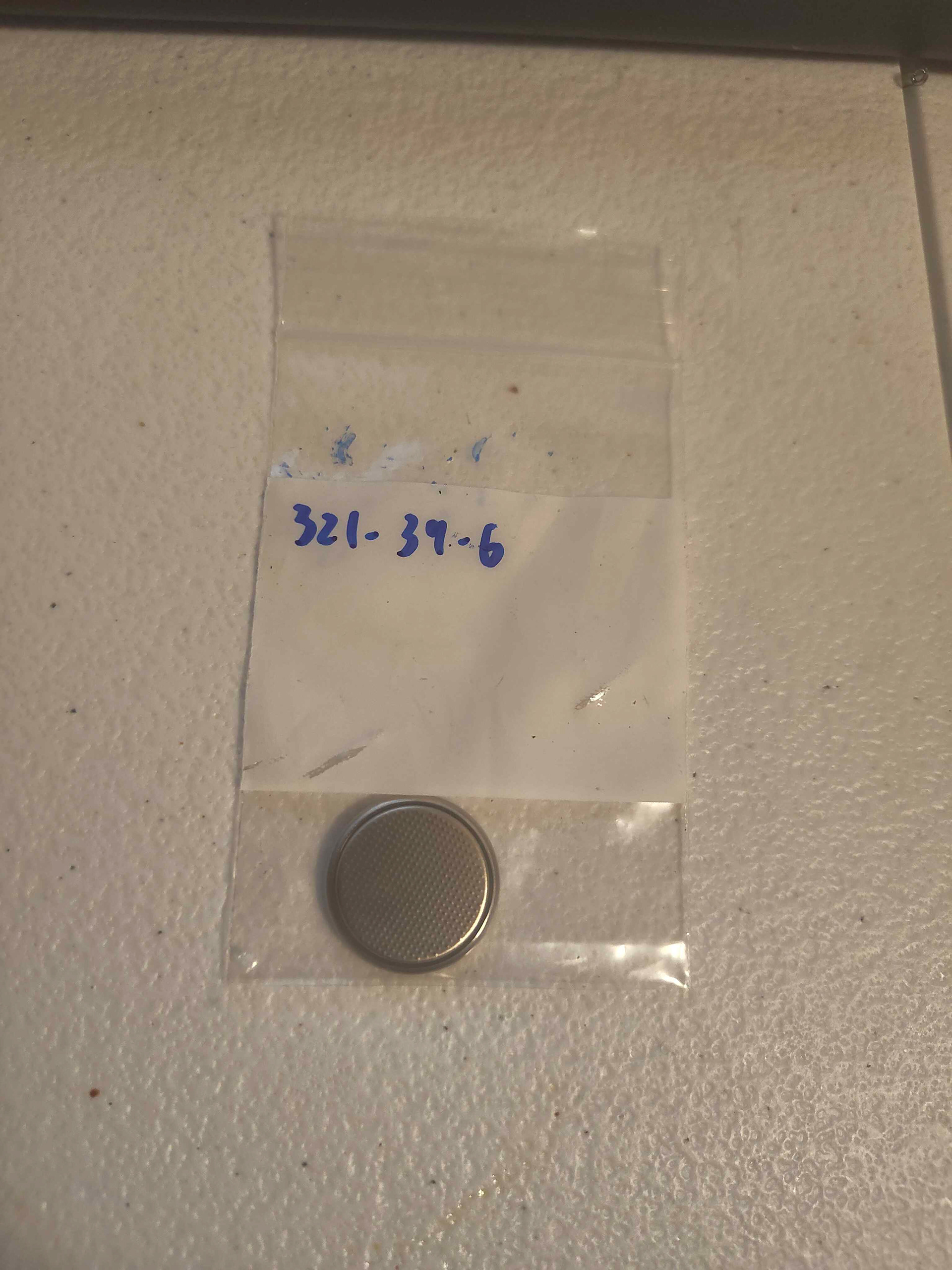

Coin cell

Coin cells utilize a single cathode layer, while pouch cells incorporate multiple stacked layers to increase capacity. This added layering introduces mechanical complexity, making cathode adhesion and structural stability critical during cycling—requirements that the primer layer was designed to address. Without sufficient adhesion, cathode delamination can lead to internal shorts that immediately disable the battery. In a set of 20 pouch cells, primer-coated cathodes shorted 60% less, suggesting that improved adhesion and reduced delamination directly contributed to enhanced cell-level reliability.